Watching Michael Palin recently, first on the trail of Hammershøi, and then sojourning in North Korea, made me remember the duelling Hemingway documentaries of the strange stressful summer of 2021.

They were only duelling because the BBC decided to re-run Palin’s 1999 documentary on Hemingway as they premiered Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s PBS series. Palin’s documentary had originally been timed to mark the hundredth anniversary of Papa’s birth. Whereas Burns and Novick’s was merely ‘what’s next’ in their insatiable curiosity. Two documentary series tackling the same subject, but offering vastly different portrayals. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s Hemingway takes an objective, historical approach; there is the inimitable Peter Coyote voiceover, the archive footage, the still photography, and the reading of letters by luminaries, including Jeff Daniels as the voice of Ernest Hemingway. Meanwhile Michael Palin’s Hemingway Adventure dispenses with any pretence to such objective journalism, displaying a characteristically personal touch; as Palin traverses continents to see what Hemingway saw, eat and drink what he ate and drank, and even wear what he wore, modelling Hemingway’s fashionable (sic) safari outfits, and in the process painting a surprisingly likeable picture of the often-gruff author. And to say other people found him gruff is putting it mildly…

Burns and Novick delve deeply into Hemingway’s turbulent life. They don’t shy away from his eventually terminal struggles with depression, his multiple failed marriages, or his obvious alcoholism. The result is a complex, deeply unflattering portrait. It is hard to stomach the vainglory of the peacocking ‘wise old man’ of A Moveable Feast recording himself in his youth in Paris as having said to himself – “All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know” – from the same man who deliberately did not report the reality of the conduct of the Spanish Civil War, even as he propagandised for the Communists, because he was hoarding their atrocities for his novel on the topic. Truth 0 – For Whom the Bell Tolls 1. We see Hemingway as a man capable of great cruelty and emotional neglect in his treatment of women. He persistently starts affairs and is out the door on one wife before she knows that he’s in the door with the next. This historical lens is crucial for understanding the man behind the myth, but it leaves viewers with a sense of Hemingway as a deeply flawed and deeply unpleasant figure. This is the Hemingway that Lillian Hellman memorably records her partner Dashiel Hammett as losing all patience with at a New York table. As Hemingway bloviates about his experiences in Spain, his great knowledge of Spain, and war, and love, and literature, and truth, and really just his general awesomeness, he eventually ends up at a highly Seinfeldian place of feats of strength: Belligerently insisting the other male diners prove their virility by matching his bending of a fork. Hammett exasperatedly sighs, “I probably couldn’t do that now. But when I could do things like that, I did them for Pinkerton money. Why don’t you go roll a hoop in the park?”

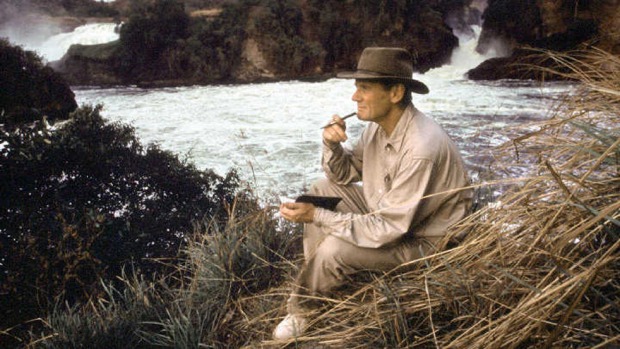

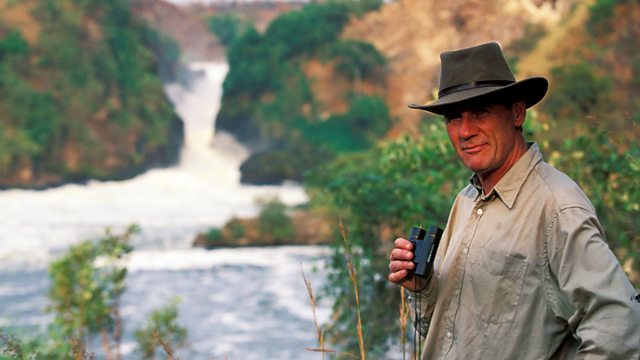

Palin, on the other hand, brings his own adventurous spirit and infectious enthusiasm to the table. He retraces Hemingway’s footsteps, travelling to the places that shaped the author’s life and work, asking random people at bullfights in Spain about their knowledge of Hemingway, and talking to people who drank with him in Cuba about their memories. Palin doesn’t shy away from the darker aspects, but his approach is more personal, almost conversational. He seems genuinely fascinated by Hemingway, finding humour and camaraderie in the writer’s larger-than-life persona. Whereas Burns and Novick wring their hands over all the head injuries; and indeed as good as imply that Hemingway’s diminished literary power and increased depressive episodes were related to the endless concussions; Palin recreates an early (actually quite Pythonesque) accident in Paris into a delirious comic set piece of flushing the skylight, as it were. This personal connection shines through. Palin highlights Hemingway’s love for landscape, his passion for bullfighting, and his deep affection for drinking companions. We see a man restlessly seeking adventure, deeply affected by war, and who craved a simpler life. Palin’s own charm softens Hemingway, making him more endearing than he really was. The contrasting approaches raise interesting questions about whether complete objectivity is possible. Palin’s series acknowledges the established facts but adds a layer of personal interpretation, and whimsy, making Hemingway feel less like a historical figure and more like a flawed friend. This doesn’t erase the darkness, but viewers see the man behind the myth with a more sympathetic eye, because Palin is not trying to see all sides of the man. When you find out that Hemingway was very short-sighted in Burns and Novick, you wonder when Palin is in the savannah how the hell Papa ever shot anything, and then Palin demonstrates the pocket for glasses that he needed, but avoided wearing in public…

Hemingway, the macho macho man. It is very easy to tire of Hemingway’s bombast and braggadocio, especially when his hypocrisy is held up to scrutiny. Ultimately, both series offer valuable insights into Hemingway’s life and work. Burns and Novick give us the warts-and-all portrait of a literary giant, while Palin’s more personal lens allows us to follow in his footsteps. One doesn’t negate the other; they offer complementary perspectives. For my own part I couldn’t help but think that it was the crucial moment of reading Hemingway that made the difference between the two approaches. Palin had to read A Farewell for Arms as a teenager for school, and in some ways he still is the enthusiastic teenager, forty years later, following his literary idol into far flung places – immortalised in trademarked prose. The explosion of a very adult world of sex and war, told in clipped, repetitive, stylised language, dripping with macho affectation and cynicism, into a 1950s schoolboy’s existence is easy to understand as the kind of intervention that lastingly shapes a worldview.

For my own part I had to read The Sun Also Rises for college, and was nonplussed by it and some short stories. Whereas Palin was wowed by Hemingway’s macho nonsense, I was left cold by it after my secondary school years spent watching reruns of The Avengers. John Steed is a very different model of being a man than Ernest Hemingway ™. To continue the bizarre association of ideas (it was a strange and stressful summer as I may have mentioned before), that show also depicted Steed & Mrs Peel as inseparable and equal, and I was revisiting it in 2021 with The Engineer, even as Burns and Novick’s rigorous documentary produced an increasing loathing from me towards Hemingway, especially how he treated women. The war correspondent Martha Gellhorn wanted to be an equal partner. Hemingway preferred slavish devotion in a wife. Friedrich Bagel and I have been having the same argument about Hemingway v Fitzgerald in coffee shops and restaurants from the IFI to Petanque for nearly two decades now. I felt maybe he was right and I had misjudged Hemingway after a revelatory adaptation of The Sun Also Rises at the 2012 Dublin Theatre Festival. So I read A Moveable Feast, and enjoyed it. And then I read A Farewell to Arms, and struggled to get thru the celebrated first chapter about as many times as Hemingway redrafted the damn thing. To me, the man had already lurched into self-parody of his style in his second major novel. And that’s before we get to the ‘character’ of Catherine Barkley, who Richard Yates justly derided in his workshops as the type of masturbatory fantasy his students should aspire not to write. I think Palin produces an endearing Hemingway because he himself is so nice. Whereas Burns and Novick produce a not very pleasant Hemingway because they are not invested.

But if you are invested, you are invested. Friedrich Bagel is invested in Hemingway. I am invested in Scott Fitzgerald. And so the argument goes on. Both are important. Both drank too much and led semi-disastrous lives. But we all still have to wrestle with the writing styles of both.